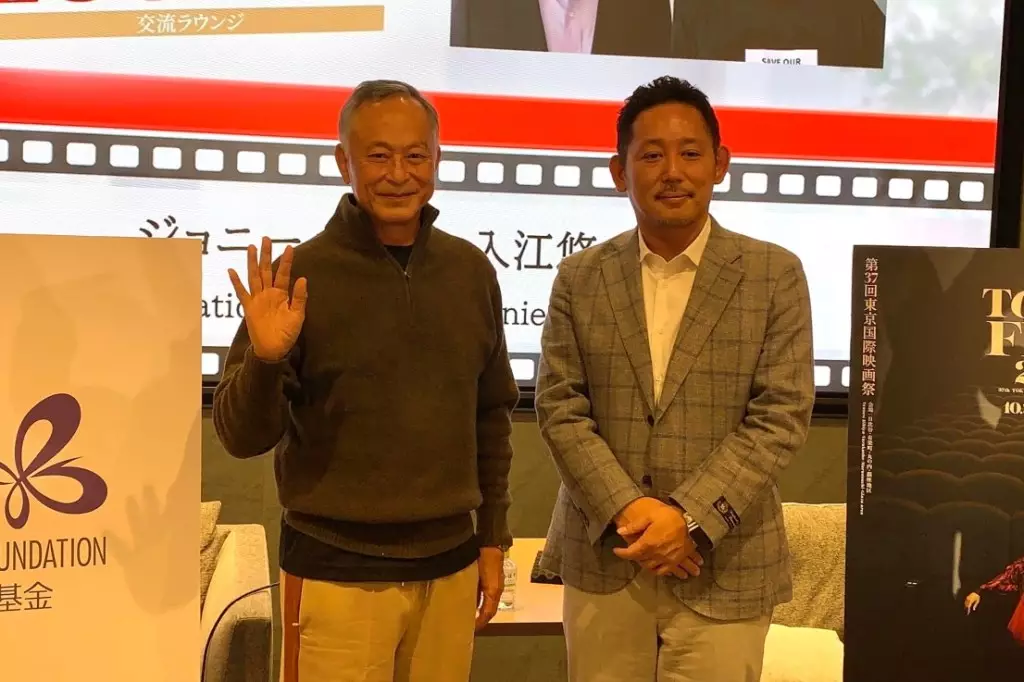

Hong Kong cinema has always held a unique position within the global film landscape, with filmmakers like Johnnie To at the forefront of its distinctive style and narrative approaches. Recently, To engaged in a thought-provoking dialogue with Japanese director Yu Irie during the Tokyo International Film Festival. Their discussion revolved around To’s extensive career, his unconventional shooting methods, and the increasingly challenging environment for filmmakers in Hong Kong. Irie’s admiration for To’s works, particularly “Exiled” and “The Mission,” underscored the significant influence of Hong Kong cinema on emerging directors, highlighting its capacity to inspire and shape future cinematic voices.

To’s confession about his somewhat chaotic filmmaking style—often opting to shoot films without a traditional screenplay—reveals a refreshing contrast to the structured approaches typically advocated in film schools. He asserted that having a complete screenplay before shooting feels like the film is already finished, which stifles his creative potential. Instead, To relies on a mental framework of the film’s structure, ensuring he identifies the crucial moments in scenes before he even calls “action.” Though this method allows for fluid creativity during production, it raises questions about the potential strain on the cast, who might find themselves grappling with uncertainty in the absence of a definitive script.

While To reminisced about his methods, he candidly acknowledged that they were not advisable for young filmmakers, promoting a sense of realism in an industry that is rapidly changing. His ability to balance multiple projects simultaneously not only underlines his versatility but also reflects inevitable compromises that filmmakers are forced to make when resources are tight. The anecdote about “Sparrow,” where he shifted between projects to secure funding, illustrates the harsh realities of independent cinema, where financial constraints can dictate the pace and direction of artistic ventures.

As To shared his experiences of filming under these pressures, it became evident that navigating the complexities of funding is just one aspect of a broader challenge faced by filmmakers in Hong Kong today. Declining freedoms and increasing censorship are emerging as significant barriers to artistic expression. In recent years, To has noticed a sharp decline in the liberties afforded to filmmakers, an observation corroborated by instances of films being subjected to censorship at local festivals. He pointed to the troubling trend of films being screened with essential scenes altered or muted, revealing the tightening grip of regulatory scrutiny.

To’s insights into the impact of censorship on creativity prompt deeper reflections on the nature of storytelling in oppressive environments. He emphasized the necessity for filmmakers to grasp the implications of censorship fully, suggesting that innovation becomes integral when navigating these boundaries. Rather than retreating or self-censoring, To advocated for a thoughtful approach—thinking critically about how to express complex ideas without sacrificing authenticity.

In an age where media can traverse borders with ease, To’s advice to young filmmakers about seeking opportunities beyond Hong Kong is a call to resilience. Rather than viewing limitations as insurmountable barriers, he suggests that aspiring artists harness their talents in other countries, such as Singapore, Malaysia, or Japan. The guiding principle remains the same: talent should not be confined by geography, and filmmakers should exploit whatever avenues they can find to tell their stories.

Despite the numerous challenges, To’s commitment to nurturing new talent remains steadfast. His establishment of the Fresh Wave International Short Film Festival signifies an investment in the future of Hong Kong cinema, providing a platform for emerging voices amid a turbulent landscape. Furthermore, his call for bolstering investment—both from the government and private sectors—is a clarion call to recognize cinema’s potential to drive cultural narratives and societal discourse.

As he approaches the milestone of turning 70, To poignantly reflects that while he still has years left to contribute to the industry, it is crucial to pave the way for the next generation. The demand for increased resources and support speaks to the broader need for a vibrant cinematic ecosystem capable of adapting to changing circumstances, not just for survival, but for thriving artistic expression.

The conversation between Johnnie To and Yu Irie epitomizes the delicate balance of artistic freedom and the daunting realities faced by filmmakers today. Through To’s unique insights, we are reminded of the importance of creativity, resilience, and the persistent pursuit of storytelling, even amid oppressive constraints. The legacy of Hong Kong cinema will ultimately depend on its ability to navigate these challenges, transforming adversity into inspiration for future directors.